Minister for Treasury Patrick Pruaitch in his 2017 National Budget speech said that there was an overarching theme of “Responsible Fiscal Consolidation” (page 4) and that the O’Neill-Dion Government was moving decisively to “move the Government Debt to GDP ratio onto a sustainable path” (page 5).

It is reported that Prime Minister Peter O’Neill is aware that his Government’s last budget cannot “buy re-election” and has stated that the “electors of Papua New Guinea today are a lot more sophisticated now than decades ago, and our citizens see through a sham and they know when politicians are spending money just to try and win votes.”

A key statistic to examine is the debt-to-GDP ratio to make an assessment of these public statements by the Prime Minister and Minister for Treasury. Fiscal consolidation means the National Government will continue to reduce the size of the national budget deficit and the Government states it is doing this with the “responsible management of the budget by bringing the total debt-to-GDP ratio in 2017 below the 30.0 per cent limit by the PNG Fiscal Responsibility Act 2006” (page 15 of Volume 1, 2017 National 2017 Budget Papers).

Nominal GDP (“NGDP”) is the total income made in our country in a year. Public debt is the sum of borrowings made by the Government that remains outstanding. Nominal indicates that the valuation of the national income and public debt are done using today’s prices. The budget deficit, public debt and other economic statistics are often scaled against NGDP to allow comparisons with other countries so we can see how PNG is performing. This allows to answers questions like “Are we at the level of similar countries?” or “Are we above the regional or global average?” and so forth.

The ratio of gross debt to nominal gross domestic product (NGDP), often simply called “debt to GDP ratio”, is computed in percentage as,

Debt – to – NGDP = Public Debt divided by NGDP x 100 (1)

This ratio measures the indebtedness of the National Government against the income of the whole country. So a ratio of 30% means that if all the public debt had to be repaid at a particular time we would need 30% of the total money made within our country to clear it.

The debt-to-NGDP ratio is a key target for fiscal policy. It determines how large our budget deficit can be and consequently the level of public spending for a year. We have a law called the Papua New Guinea Fiscal Responsibility Act 2006 (with an amendment by the O’Neill-Dion Government in 2013) that sets this ratio at 35% for years 2013-2015 and then 30% for 2016 and 2017.

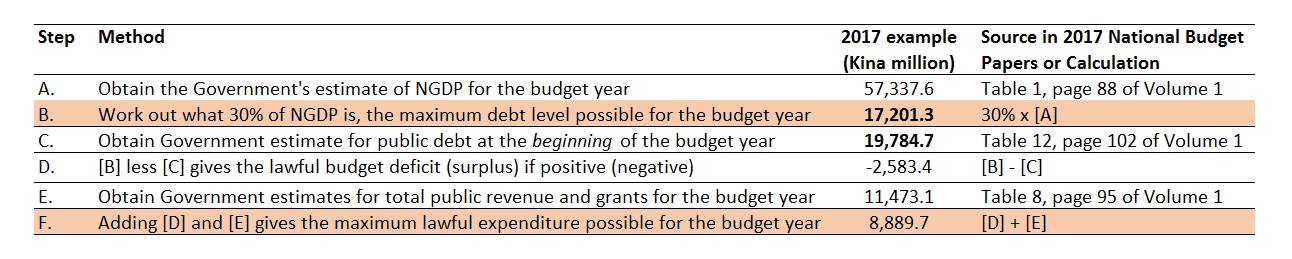

I outline the basic steps the Government could follow to set the maximum lawful level of public expenditure in the National Budget in Table 1 using as an example the Government’s own raw data (i.e. without correcting any mistakes in them) from the 2017 National Budget.

Table 1

Source: 2017 National Budget Papers and author’s calculation

What is apparent from Table 1 is that the nominal GDP (NGDP) matters for determining the maximum budget deficit and public expenditure possible. In this example the NGDP statistics has been taken from Table 1 of Volume 1 of the 2017 National Budget and shows that the Government’s budget should be a surplus next year and not a deficit as is planned. The results in Table 1 also shows that the Government’s planned 2017 public expenditure is set too high by nearly K4.5 billion. However, this result is derived using the Government’s principal estimate of the 2017 NGDP and when the second unexplained estimate is used (as the Government does) then this breach disappears.

There are other ways to finance the deficit including asset sales but doing this reduces the net worth of National Government if not used for productive public investment. I have also discussed asset sales for 2016 and its incorrect fiscal accounting by National Government in an earlier blog post. Without asset sales the principal means of funding the budget deficit is by the Government borrowing.

There will only be a budget deficit (and new borrowing) if public expenditure is greater than public income, which has been the case for most years. If NGDP is growing faster than the rate of increase of Government debt than this is not a problem – and this has generally been the case for PNG. So we don’t need to panic if there is a budget deficit as we only need to ensure that the size of the budget deficit does not take us beyond the 30% debt-to-GDP mark set by law.

Is the debt-to-nominal GDP limit breached?

So is there a breach of the debt limit in the 2017 Budget?

Looking through Volume 1 of the 2017 National Budget documents I am having difficulties understanding if there is a breach or not. Most troubling of all is that Government trips over itself suggesting that it too doesn’t seem to know.

From the formula given above, we know that to compute the debt-to-NGDP ratio we need to look at: (1) the projected debt level at the end of 2017; and (2) the estimate for nominal GDP for 2017.

The Government seems fairly confident about its projected debt levels, as you would expect, and I’ve used the public debt numbers that appear in Table 12 on page 102 of Volume 1 of the 2017 National Budget papers in my computations.

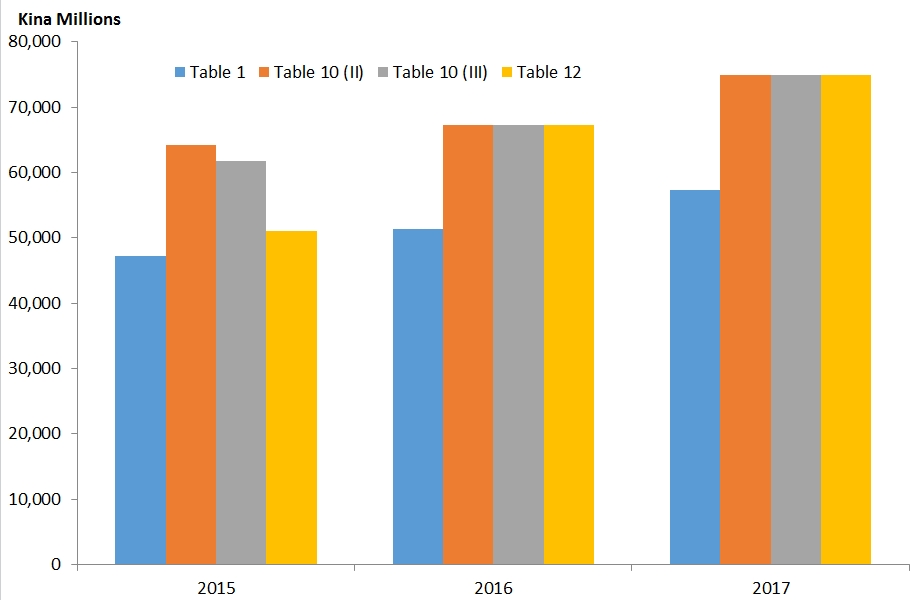

Now we need the nominal GDP numbers but the Government’s official document on the Budget has different numbers for nominal GDP in the statistical tables that appear on pages 88, 99, 100 and 102 of Volume 1 of the 2017 National Budget papers, as shown in Figure 1. The Government should have only one number for nominal GDP in each year.

The principal source for the GDP statistics is Table 1 on page 88 of Volume 1 as this is only table with the details of components of GDP – there is no other table with this information. Moreover, these numbers are consistent with the numbers that appear throughout the text in Volume 1 and also cited by the Minster for Treasury in his 2017 budget speech. I noticed that whilst the Minister for Treasury discussed 2016 real economic growth (page 2 of his speech) he failed to discuss economic growth for 2017 – an extraordinary omission for the 2017 National Budget.

Figure 1

Source: Volume 1 of 2017 Budget Documents and author’s calculations

The nominal GDP estimates by National Government vary with 4 different estimates for 2015 and two different estimates for nominal GDP for 2016 and 2017 made by the Government. I’ll talk about the GDP numbers in a different post and try to make sense of them. If these different sets of nominal GDP numbers are used for the debt-to-GDP ratio we get the results presented in Figure 2.

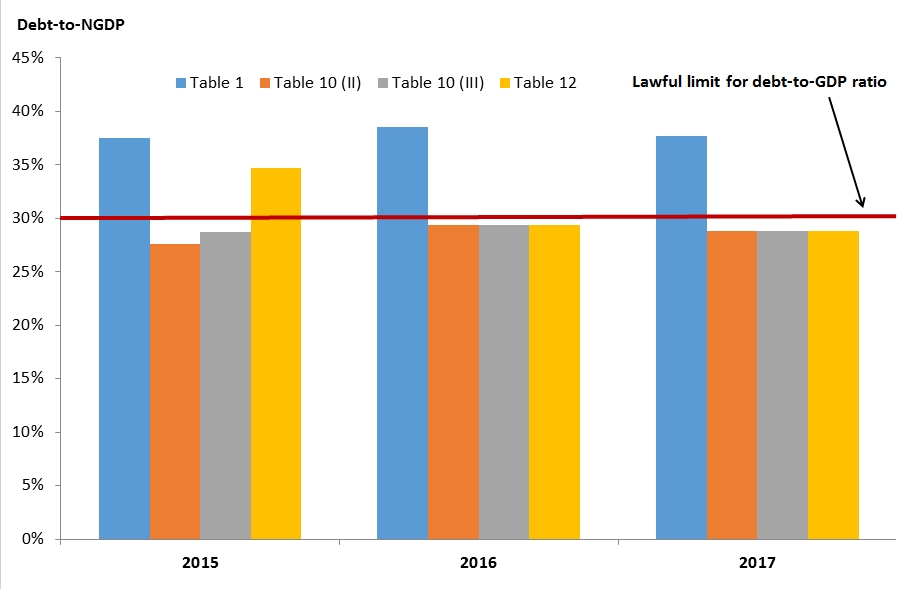

Figure 2 shows that the Government may have breached the 35% limit of debt-to-NGDP for 2015 and may breach the limit of 30% at the end of 2016. It also shows that the Government is or will be in breach of the debt limit of 30% for 2015-2017 if it uses the nominal GDP estimate shown in Table 1 of Volume 1, the Government’s principal and only complete GDP data estimates.

It is not explained in Volume 1 how the alternative nominal GDP number that appears in Tables 10 and 12 are derived and why it is different to the principal GDP data source, i.e. Table 1. Using Table 1 for nominal GDP numbers, for 2017 the debt-to-GDP ratio will be 37.7%, above the legal limit of 30%.

Figure 2

Source: Volume 1 of 2017 Budget Documents and author’s calculation

The worst possible perception, which I stress I do not make, is that the Government is doctoring the books to present an illusion that it is complying with the lawful limit for debt. This is highly damaging for the Government’s credibility with increasing global attention now being paid to Papua New Guinea as it prepares to host the APEC Summit in 2018.

Is this yet another extraordinary blunder by the Government that contradicts Prime Minister Peter O’Neill’s public statements?