From my The PNG Woman column in the Sunday Chronicle, 21 May 2017

“It’s the economy stupid” became the rallying slogan for Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 presidential campaign. A growing economy represents growing national income and remains a necessary condition to improve the well-being of Papua New Guineans through expanded incomes and job creation. The Government through its policy choices can make a substantive difference to whether this growth is inclusive and sustainable (both economically and environmentally). The size and nature of public investments and other government spending as well as the policy and regulatory environment can determine the pattern of growth and how the gains from economic growth are distributed amongst sectors, industries and most importantly our people.

“It’s the economy stupid” became the rallying slogan for Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 presidential campaign. A growing economy represents growing national income and remains a necessary condition to improve the well-being of Papua New Guineans through expanded incomes and job creation. The Government through its policy choices can make a substantive difference to whether this growth is inclusive and sustainable (both economically and environmentally). The size and nature of public investments and other government spending as well as the policy and regulatory environment can determine the pattern of growth and how the gains from economic growth are distributed amongst sectors, industries and most importantly our people.

The economy occupies center stage in debates in elections worldwide. This is hardly surprising. Often the economy plays a major role in determining the outcome of election results. Why? Because the political rhetoric and spin cannot change the realities on the ground – how our people are deeply impacted by economic growth. Losses of job or declines in real income can severely undermine the quality of life of Papua New Guineans. The ability of the economy to provide jobs for a growing workforce is of paramount concern. A growing economy can result in more tax income to fund essential public services and goods. Economic performance and the incumbent government’s role in engendering this is fundamental in the concerns of our people.

The Government in trying to expand into all parts of the economy cannot substitute for a reduced or even lost income of our people and their ability to choose the lifestyle they want. Yes we know of market failures but the sins and costs of government failure can be far worse. A balance needs to be found. The private sector must be the engine of growth. Micro, small medium enterprises provide the bulk of employment in many countries and in Papua New Guinea this sector growing remains the best means for engaging our growing labour force. Our people don’t want handouts they want a hand up – an enabling environment offers the best prospects for shared prosperity.

It is enshrined in our Constitution that we have freedom of expression. For a central bank Governor to attempt to stymie discussion of substance that is crucial to the choice of political representation that Papua New Guineans have in Parliament is disturbing. It is an assault on democracy.

When we examine the conduct of the Bank of PNG in implementing monetary and exchange rate policy we are compelled to question the independence of the central bank. Make no mistake this is a matter of serious concern. Independence here refers to either goal independence or instrument independence. The broad goals of the Central Bank are set out in its enabling legislation but there is some discretion, for example, BPNG is responsible for price stability but the Central Banking Act does not specify what inflation rate this should be. Instead the Governor sets out his definition and target in the semi-annual policy statements he issues.

The second dimension of independence surrounds instrument independence. All this means, for example for price stability, is that BPNG can choose the policy tools it wants to use. Given the bluntness of its policy interest rate, the BPNG says it relies on controlling the money supply to influence inflation outcomes. However, BPNG’s research (see here) indicates that the key transmission mechanism for inflation is the exchange rate, which the BPNG also controls. In this regard, BPNG has instrument independence.

There are many different ways to measure the independence of a central bank and one measure (see here) uses the four criteria (based on the legal framework):

- a central bank is more independent if the Governor is appointed by a Central Bank Board rather than the Government so he cannot be dismissed easily and has a long term of office – these help quarantine the BPNG from political pressure;

- independence is higher the greater monetary policy decisions are taken without government involvement;

- if the goal of price stability is the primary goal of monetary policy; and

- if there are limitations on funding the budget deficit.

On this scorecard, in law, BPNG fails (1) but satisfies (2), (3) and (4). This would seem on the face of it a good result. However, the actual conduct of BPNG against the last three criteria is problematic.

The significance of government appointing the BPNG Governor should not be understated. Loi Bakani was reappointed last year and unconfirmed whispers are that only this month the O’Neill Government extended his second term from 5 years to 7 years. In recent years Bakani has been the principal fiscal cheerleader for the O’Neill Government usurping at times the official fiscal spokesperson role of the decommissioned Treasurer, Patrick Pruaitch, and even that of the Department of Treasury Secretary.

The question does arise as to whether these circumstances played a role in Bakani’s statements and conduct. Irrespective of this, the timing of the Bakani’s public statement is clearly inauspicious and misguided. It raises the obvious question of the independence of the Central Bank and of a possible conflict in the discharge of the duties of Bakani as the Governor.

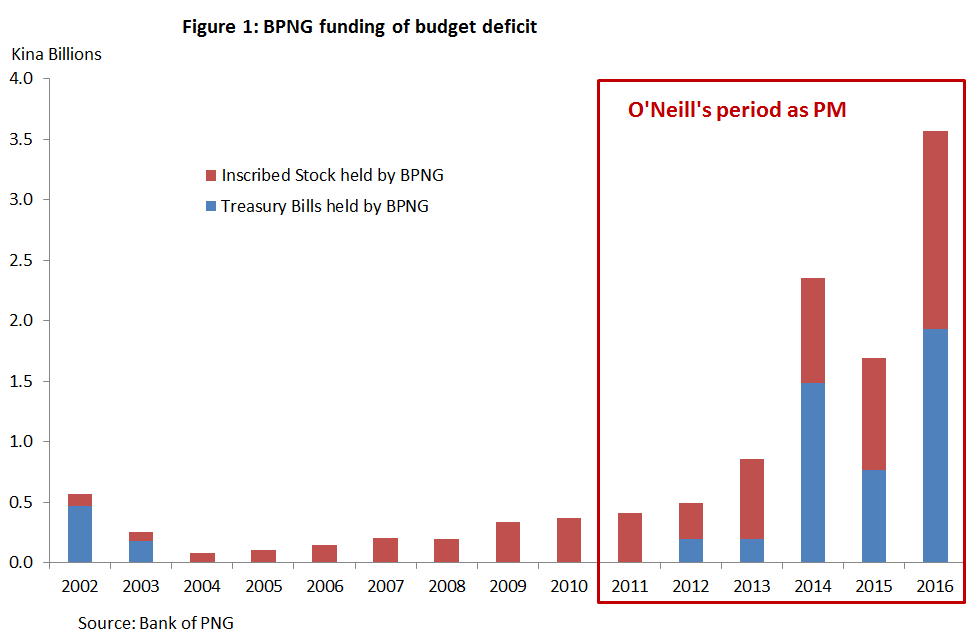

So let’s look at criteria (4). Section 55 of the Central Banking Act (see here) explicitly states that BPNG shall not provide an advance to Government to fund the budget deficit beyond an amount set by regulation, this is around K200 million I believe. However, we see from BPNG’s own statistics that it provided K1.9 billion in 2016 to prop the Government up. In 2014 it provided K1.5 billion in funding to the Government. These are excessive amounts and surely in breach of the Act.

The Bank of PNG also breached its Act in paying a dividend of K102 million in 2014 (see here). The Central Banking Act prohibits the payment of a dividend unless the assets of BPNG exceeds the liabilities and paid up capital. In the 2013 Annual Report this condition set by law is exceeded by K447 million and again in the 2014 Annual Report by K410 million. There are some serious questions that need to be asked of the BPNG Board and its Executive Chairman Bakani.

I was further astonished to see that the BPNG reports that the Government owes it K1.12 billion that has not been outlined in the Government budget. It says it is a promissory note, which seems to be contingent liability but the magnitude is so great that it should have been disclosed more visibly to Parliament and the people of Papua New Guinea.

Criteria (2) is also seemingly being undermined by the increased participation of the central bank in budget financing matters. Pruaitch, the immediate former Treasurer, savaged Bakani for failing to deliver the debut sovereign bond but did not voice that it seems improper to have the central bank responsible for the sovereign bond. This is a fiscal matter and should be handled by the Treasurer and his Department. This undermines the ability of the BPNG to refuse to provide a large fiscal advance to Government when it is responsible for securing the large off-shore borrowing to fund the deficit that will be used to repay itself as well as to prop up foreign reserves. This overlay of roles has clouded the impartial conduct of monetary policy.

The call by the BPNG Governor to refrain from discussing the economy only invites a closer look his abject performance and for an explanation as to why under his watch BPNG has broken its governing law. Bakani’s former boss Pruaitch said Bakani’s improper statement was an assault by proxy. I view it as twin assault on an independent institution and our democracy.